Virtue-Based Psychosocial Adaptation Model

The Virtue-Based Psychosocial Adaptation Model (V-PAM) is developed based on various research findings, and it provides a theoretical framework of virtue-based psychosocial intervention designed to promote post-traumatic growth (PTG) after

life adversities such as chronic health issues, disabilities, and PTSD. V-PAM explicates post-traumatic growth and psychosocial adaptation after life adversities in terms of five virtues (i.e., courage, integrity, practical wisdom,

committed action, and emotional transcendence).

Philosophical Underpinning

In comparison to Plato’s view, the following five characteristics are unique to Aristotle’s perspective on virtue ethics:

1) A teleological worldview (Johnson, 2005),

2) Nicomachean ethics (Aristotle, 350BC/2009),

3) An emphasis on Voluntarism (Crisp, 2013),

4) A perspective on practical wisdom (Fowers, 2005), and

5) Realism (Tweedale, 1988).

A teleological worldview believes that in order to determine whether an action is good or bad, one has to consider the purpose and consequences of the action, rather than considering actions as being inherently good or bad (deontology)

(Johnson, 2005). In addition, Nicomachean ethics views the goal of human activity to be happiness, which is rooted in the thing that makes us most human – our intellect and our reason (Aristotle, 350BC/2009).

Within the V-PAM, these

two perspectives provide a fundamental lens through which the disability can be viewed.

The onset of disability is obviously a challenging experience. However, although it may take time, a rehabilitation counselor can assist an individual, who might otherwise view this life change as unavoidably resulting in unhappiness, to see disability and life advesity as an opportunity for future growth. Voluntarism is also one of the most important philosophical foundations in virtue ethics, and it emphasizes the importance of action. Thus, virtue ethics and the V-PAM are based on the idea that there is no virtue without action, and there is no virtue-based adaptation without a course of action to address the challenges that may accompany the onset of disability. Furthermore, a course of action needs to be determined based on an individual’s best judgment (i.e., practical wisdom perspective) given an understanding of her or his current life context (i.e., realism).

With the onset of disability, life often becomes unpredictable and filled with various challenging circumstances. The V-PAM views the most fundamental human capacities to deal with such situations as the ability to have a constructive

mindset that views disability as a new opportunity (teleological worldview, Nicomachean ethic perspective), and to deliver a course of action (voluntarism) based on the contextual understanding of an individual’s life circumstances

(practical wisdom & realism). This process can be facilitated and promoted through a collaborative rehabilitation counseling. This collaboration highlights the vital role and function of a rehabilitation counselor in terms of promoting

psychosocial adaptation after the onset of disability.

Theoretical Underpinning

(b) developing the best course plan, and

(c) acting upon their values.

Furthermore, living virtuously does not always produce ideal outcomes due to the influence of internal and external factors. From a virtue perspective, living and behaving by one’s values ultimately leads an individual to emotional concordance. Consequently, failure can also be a source of future growth. According to Aristotle, a consistent effort to live virtuously and self-actualize leads to a flourishing life (Fowers, 2005).

One of the challenges in applying this concept to behavioral and psychological science is to explain what constitutes a virtuous life.

Action is not only a central principle in virtue ethics but it also distinguishes virtue from value. Value is what one believes to be important, but it does not necessarily translate behaviorally (Adams, 2006). Virtue, however, represents

how one lives by their values. In other words, one must incorporate values in their actions (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Practical Wisdom involves (a) one’s cognitive processing to understand life circumstances, and (b) developing

the best course of action. In doing so, a person must consider both the resources and challenges that are situated in the individual and those that originate from the relationships, systems and community outside of the self. This need

to consider both the intraand interpersonal aspects that may affect the wisdom. This consideration is the reason that the “communal aspects of virtue” is emphasized because the community and its relationship to the individual’s values

are where an individual’s effort to live virtuously may be complimented and supported. Fowers (2005) also stated that sustaining a virtuous life is not an easy task; thus, it requires emotional cultivation. For instance, even in a

challenging situation, virtuous persons can make positive and growthful decisions by acting upon their values. Therefore, they are able to reach a state of concordance between their thoughts, emotions, and actions. That is why a person

can feel that they are living virtuously while at the same time they are consistently actualizing themselves.

This perspective is similar to Maslow’s self-actualization theory. Maslow (1968) stated that every human has a desire to self-actualize. In his theory, self-actualization is defined as the “fulfillment of the ongoing actualization of potentials,

capacities, and talents,; as fulfillment of mission (or call, fate, destiny, or vocation); as a fuller knowledge of, and acceptance of, the person’s own intrinsic nature,; and as an increasing trend toward unity, integration, and synergy

within the person” (Maslow, 1968, p. 25). Maslow further indicated that self-actualization is “a slow process taken one small painful step after another into the dark unknown” (Fernando & Chowdhury, 2015, p. 5). Self-actualization

and virtuousness are similar in that both emphasize consistently meeting one’s needs to become a better and superior being. Thus, Ivey (1986) viewed Maslow as an Aristotelian virtue ethicist.

Five V-PAM Virtues

To reshape Aristotle’s virtue perspective into a post-traumatic growth and psychosocial adaptation model, the four key components (i.e., action, practical wisdom, communal aspects, and emotional cultivation) that constitute a virtuous

life were redefined to fit a rehabilitation counseling perspective. Plus, one additional component, Courage, was added.

Committed Action. There is no virtue without action (Adams, 2006). The Action component was renamed to Committed Action. It is defined as one’s dedication to delivering a constant effort to accomplish a goal, despite the

presence of obstacles. Becker and Van Dick (2006) described commitment as “a force that binds an individual to a target (social or non-social) and to a course of action of relevance to that target” (p. 666). From a counseling perspective,

Giacomo and Weissmark (1992) examined the mechanism of committed action by measuring clients’ degree of treatment involvement. In comparison to unsuccessful clients, successful clients showed a more robust degree and quality of participation

in the counseling process. In the V-PAM, consistency in one’s behavior is seen as being indicative of long-term commitment to pursuing excellence and living well following the onset of disability and/or illness. In other words,

the constant pursuit of excellence is a key concept of

Committed Action (Adams, 2006).

Emotional Transcendence. Emotional cultivation was renamed to Emotional Transcendence. This term encompasses the ability to infuse new hope into life and to transform adversities into insights and renewal, even in the

face of difficulties (Kim, McMahon, Hawley, et al., 2016). According to Hanfstingl (2013), transcendence involves mental information processing, motivational forces, and the acquisition of higher transcendental experiences that foster

psychological resilience. Transcendence improves one’s perception of the past, present, and future, which ultimately enhances self-worth and connectedness. Thus, emotional transcendence helps individuals to create meaning in their

lives and to reach emotional and mental congruence (Coward, 1990; Fowers, 2005; Reed, 1991).

Practical Wisdom. Although there were no nomenclature changes, the meaning of Practical Wisdom was extended to include one’s ability to use knowledge and experience to make an informed decision relevant to their situation.

The practice of virtue is often vague in real life (Livneh & Martz, 2016). Thus, practical wisdom entails one’s ability to formulate a suitable situational decision (Fowers, 2005). However, the best decision in one situation might

not be appropriate under different circumstances. Thus, Practical wisdom emphasizes relying on one’s moral compass to guide appropriate action by facilitating the metacognitive processes relevant to situational appraisals, strategic

problem solving, and self-awareness (Wells, 2009).

Integrity. The communal aspect of virtue was renamed to Integrity in the V-PAM. Integrity is defined as one’s ability to act genuinely and sincerely consistent with one’s moral and ethical standards. In turn, this integrity,

which is a primary determinant of trust, promotes healthy inter- and intrapersonal relationships (Barnard et al., 2008). A person with integrity demonstrates moral reflectiveness, and thus understands the impact of their behavior in

relation to others. Integrity also means that there is congruence in one’s behavior and relevant values. According to Peterson and Seligman (2004), a person with integrity shows a regular pattern of behavior that is consistent with

espoused values and which treats others with care, as demonstrated by helping those in need. Clearly, Integrity is a vital component in developing a collaborative working alliance within a rehabilitation counseling context.

Courage. A new concept, Courage, was added to reflect better the unpredictable nature of disability in one’s life. In the V-PAM, it is defined as one’s ability to execute will power to initiate an action despite the uncertainty

of its outcome. Although it is often viewed concerning one’s ability to face fear, Shelp (1984) states that a courageous person may not be necessarily fearless or fearful. Instead, they attempt to master fear and act despite

some level of fear being present. Woodard and Pury (2007) defines courage as “the voluntary willingness to act, with varying levels of fear, in response to a threat to achieving an important, perhaps moral, outcome or goal” (p. 136).

Thus, courage only exists with some degree of fear.

Counseling Model

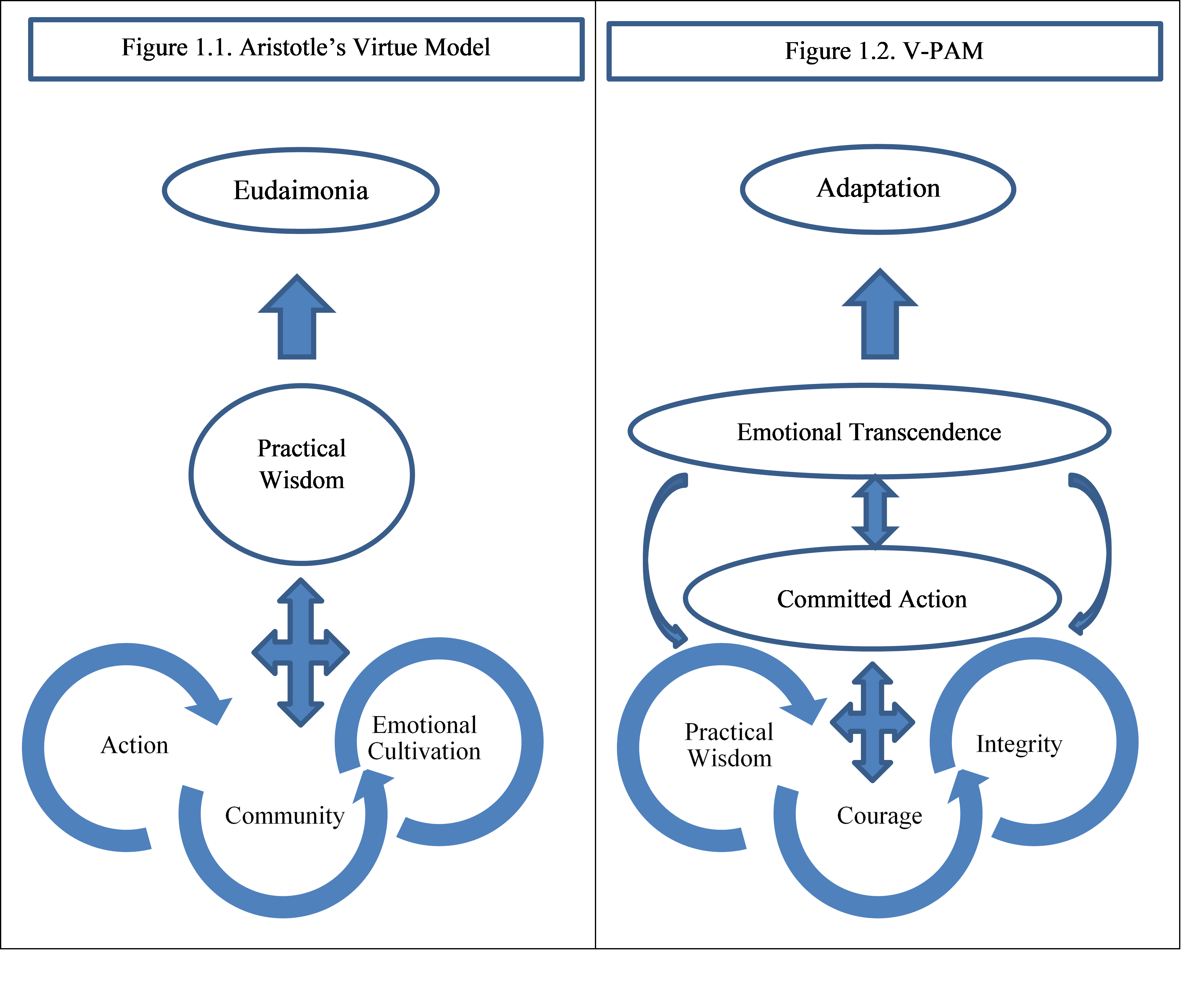

Considering the nature of each V-PAM factors in rehabilitation counseling, the interactive relationship between V-PAM factors was examined. For example, practical wisdom was considered from the metacognitive aspects of one’s life.

Particularly, it emphasizes both the contextual and unbiased judgment as well as the decision-making process. Integrity was viewed from a relational and environmental aspect of life. Courage and committed action were viewed from

a behavioral perspective, and emotional transcendence from the emotional and spiritual aspects of an individual. Moreover, V-PAM factors were realigned in terms of their relationship shown in Figure 1.

Practical wisdom and Integrity were placed horizontally as these constructs enhance one’s ability to see a new intra- and interpersonal life situation after the onset of disability. Courage and Committed Action were

placed vertically as courage ignites action, and commitment is required for long-term action. Consequently, the interaction between these four components needs to be constructively processed. As illustrated, Emotional

Transcendence was placed vertically with interactive arrows between the Emotional Transcendence and four other components to highlight the reflective V-PAM cycle. Then, to emphasize a rehabilitation perspective,

Eudaimonia (i.e., a flourishing life) was changed to Adaptation. An individual can be guided via a collaborative rehabilitation counseling relationship and grow through this cycle. Figure 1 illustrates how the customary

view of virtue ethics (Figure 1.1) was adapted into a rehabilitation counseling framework (Figure 1.2).

In summary, the three essential components in defining the nature of adaptation after life adversities in the V-PAM are 1) action (i.e., courage and committed action), 2) contextual and relational understanding of one’s situation (i.e.,

practical wisdom and integrity), and 3) constructive processing (i.e., emotional transcendence). These components are not independent, but rather are interdependent and mutually complementary. People develop maladaptive behaviors

after the onset of disability when a person 1) is not able to understand his or her situation contextually, 2) does not engaged in actions consistent with his or her values and context, and 3) does not reflect on his or her experience

to promote improved emotional well-being and future growth.

Reference

- Adams, R. M. (2006). A theory of virtue: Excellence in being for the good. Oxford University Press.

- Aristotle. (2009). The Nicomachean ethics (D. Ross, Trans). (Original work published 350 BC). Oxford University Press.

- Barnard, A., Schurink, W., & Beer, M. (2008). A conceptual framework of integrity. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 34(2), 40-49. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v34i2.427

- Becker M. J. T. and Van Dick, R. (2006). Social Identities and Commitments at Work: Toward an Integrative Model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5), 665-683. https://doi.org/10.1002/job Coward, D.D. (1990). The lived experience of self-transcendence in women with advanced breast cancer. Nursing Science Quarterly, 3(4), 162-169. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0894318 49000300408

- Crisp, R. (2013). The Oxford handbook of the history of ethics. Oxford University Press.

- Fernando, M., & Chowdhury, R. M. (2015). Cultivation of virtuousness and self-actualization in the workplace. Handbook of Virtue Ethics in Business and Management, 1-13.

- Fowers, B. J. (2005). Virtue and psychology: Pursuing excellence in ordinary practices. American Psychological Association.

- Giacomo, D., & Weissmark, M. (1992). Mechanisms of action in psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice & Research, 1(1), 37–48.

- Hanfstingl, B. (2013). Ego and spiritual transcendence: Relevance to psychological resilience and the role of age. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/949838

- Ivey, S. D. (1986) Was Maslow an Aristotelian? Psychological Record, 36, 19-26.

- Johnson, M. R. (2005). Aristotle on Teleology, Oxford University Press.

- Kim, J. H., McMahon, B. T., Hawley, C., Brickham, D., Gonzalez, R., & Lee, D. H. (2016). Psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability: A virtue-based model. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 26, 45-55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-015-9622-1

- Livneh, H., & Martz, E. (2016). Psychosocial adaptation to disability within the context of positive psychology: Philosophical aspects and historical roots. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 26(1), 13-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-015-9601-6

- Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being. Van Nostrand.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

- Reed, P.G. (1991). Toward a nursing theory of self-transcendence: Deductive reformulation using developmental theories. Advances in Nursing Science, 13(4), 64-77. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-199106000-00008

- Shelp, E. E. (1984). Courage: A neglected virtue in the patient—physician relationship. Social Science and Medicine, 18, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(84)90125-4

- Tweedale, M. (1988). Aristotle’s realism. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 18(3), 501-526.

- Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Guilford Press.

- Woodard, C. R., & Pury, C. L. S. (2007). The construct of courage: Categorization and measurement. Counseling Psychology, 59(2), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.59.2.135